-

Homepage

-

Blog

-

5 Questions & Answers To Prepare You For A Monetary Approach Quiz

5 Questions To Help You Prepare For An Online Exam On Monetary Approach To The Balance Of Payments

Passing a monetary approach to balance of payments exam requires effective preparation and revision. We are committed the academic success of our clients. It is for this reason we have posted perfectly-solved test questions on monetary approach to balance of payments. Use our questions with answers to prepare for your upcoming quiz.

Explain in detail the monetary approach to balance of payments and how it differs from the Keynesian balance of payments theory

The Keynesian balance of payments theory concentrates on the market for goods. The principal effect of an exogenous increase in exports would be to change income through the multiplier process. It was not always thus. In the classical world of David Hume trade deficits were associated directly with money supply changes.

Consider a pure gold standard world in which gold is both internal and external money. If the domestic economy developed a balance of payments surplus, a classical economist would point to the fact that the domestic gold stock would be rising by the amount of surplus per period. In other words, any imbalance in the value of goods flows is matched by net money flows in the opposite direction. The adjustment process from here on would be automatic since the rise in the domestic money stock would raise domestic money prices and cause a substitution of foreign for domestic goods. Thus, the balance of payments surplus would disappear. This is the price-specie flow mechanism' of Classical economics.

Notice that where the internal and external money is the same, the balance of payments is not a problem per se. Outflows of bullion may have banking crises and contraction of the money stock may have caused unemployment, but the balance of payments was no more a problem in the pure gold standard world than the balance of payments of East Anglia is today. There was, of course, a problem when paper backed by gold began to circulate as money because external payments required bullion. As a result, the reserve ratios of banks came under pressure whenever gold left the country. However, this was not an 'official sector problem as reserve outflows under fixed exchange rates would be today.

In the modern world, where each nation-state has its own fiat money. it might be thought that there has to be a connection between the domestic money stock and the balance of payments. However, this is not generally true if the authorities are intervening to support the domestic exchange rate.

Discuss the process of pegging and exchange rate in the UK.

The process of pegging an exchange rate means that, in the UK case, the Bank of England takes up the residual excess demand or supply of foreign exchange at or close to the pegged price. If the United Kingdom has a balance of payments surplus, the authorities would buy foreign exchange with newly issued sterling. The foreign money would go into reserves and the sterling would go into the domestic money supply, so long as it is spent on UK goods (as opposed to being held overseas). The new increase in the money supply could be 'sterilized' by open market bond sales but this is of limited effectiveness where capital is perfectly mobile since the process of selling more government debt would raise domestic interest rates and thereby induce additional capital inflows - thereby putting further upward pressure on the currency and requiring further purchases of foreign exchange.

The monetary approach points out that since the balance of payments has monetary effects, and is indeed a monetary 'problem', the domestic demand for money (or indeed other assets) should be an integral part of the balance of payments analysis. If money continues to flow across the international exchanges then domestic money markets cannot be in equilibrium. An excess supply of money domestically will be reflected in an outflow across the exchanges. As the earlier absorption approach' (Alexander, 1952) emphasized, the balance of payments on the current account is by definition equal to the difference between what the economy earns (output) and what it spends (national expenditure). Any group or individual for whom income and spending differ will be changing asset holdings. The decisions to spend or save out of a given income are not independent. However, specifying asset choices and expenditure decisions simultaneously offers important insights. The Keynesian approach focused explicitly on expenditures. The monetary approach emphasized asset stocks, especially money.

Which is the most influential single contribution to the monetary approach?

The most influential single contribution to the monetary approach is that of Johnson (1976). He considers a highly simplified world in which there are rigidly fixed exchange rates and all goods are traded at a single world price. Real income growth is exogenous. The domestic money demand function is given by:

Md=pf(Y,r) (6.3)

Real money demand depends upon real income and the rate of interest.

and the money supply is given by definition as the sum of money domestically created and money associated with international reserve changes.

Ms=R+D (6.4)

Money stock is equal to reserves plus domestic credit.

If the system is in static equilibrium money demand will equal money supply and there will be no reserve changes. If, however, domestic income is perpetually growing, with constant world prices and interest rates, Johnson shows that the growth in reserves will be positively related to domestic income growth and negatively to credit expansion.

gr=α0nygy-α1gd

where gr, gy, and gd, are the growth rates of reserves, income, and domestic credit respectively, and ny is the income elasticity of demand for money.

This is a remarkable conclusion that implies that real income growth alone improves the balance of payments and is in stark contrast to the Keynesian model above, where a rise in income has exactly the opposite effect. How does this result come about? Very simply, if there is real income growth, at constant price and interest rate levels, then there will be growing demand for money for transaction purposes. An excess demand for money can be met in one of two ways, either through domestic credit creation or through a balance of payments surplus. If there is no domestic credit expansion, reserves will grow in line with the growth in money demand. The existence of an excess demand for money means that people will be spending less than their income. For the country as a whole, there will be a balance of payments surplus. If, on the other hand, domestic credit expands faster than money demand, then there will be a loss of reserves through a balance of payment deficit. The problem, then, which causes the balance of payments deficits and associated reserve losses is not income expansion itself but rather the authorities' policies for domestic credit expansion. If domestic credit expands faster than demand for money balances, there will be a balance of payments deficit and associated reserve losses.

The monetary approach under fixed exchange rates should be thought of as a theory of reserve changes rather than the trade balance since it is not clear from the literature whether the effects will appear in the current or capital account. However, it should be obvious that many of the simplifying assumptions in the Johnson model are not at all critical. Indeed, a wide range of possible macroeconomic models will have similar properties, at least in the long run, so long as they include a monetary sector that generates a stock demand for money.

The monetary approach does, however, resolve for us the apparent paradox of fast-growing countries which appear to have a perpetual balance of payments surpluses, though it does not tell us where this growth comes from. Indeed this approach predicts exactly this outcome, so long as the domestic monetary authority restricts the growth of domestic credit to less than the growth in money demand. Thus, in countries like West Germany in the 1960s, since fast growth in real income caused a growth in demand for money for transaction purposes, the economy induced an inflow of money via the foreign balance to the extent that this money was not created by the Central Bank. Since the economy was trying to acquire financial assets it would be spending less than the value of its output which is identical to running a balance of payments surplus. This surplus could be sustained because growing income required ever-growing money balances. The United Kingdom was the opposite - slow real growth and faster domestic credit expansion leading to a perpetual balance of payments problems.

Discuss the policy implications of flexible exchange rates

Much of the above discussion has presumed the existence of fixed exchange rates. The widespread variability of exchange rates since 1971 has required a great deal more attention to be paid to flexible exchange rates and their policy implications. An endogenous treatment of the exchange rate, of course, requires an explicit model of the market in which it is determined- the international money market. Modern literature on the exchange rate developed out of the monetary approach to the balance of payments. A collection of early work in this area is provided by Frenkel and Johnson (1978) and a recent survey is available by MacDonald (1988).

The traditional textbook analysis of the exchange rate derives certain propositions about the flow demand for foreign exchange from the demand for imports and exports. Suppose there are two countries, the United Kingdom and the United States. There is trade in goods between them Each has a different domestic currency and the domestic currency price of domestic output is assumed to be fixed. The United Kingdom demands Us goods but the sterling price in the United Kingdom depends upon how much UK citizens have to pay for dollars. The higher the price of dollars the more expensive will be US goods in the United Kingdom, and vic versa. UK citizens demand a flow of dollars to pay for their imports and US citizens demand a flow of sterling to pay for UK exports.

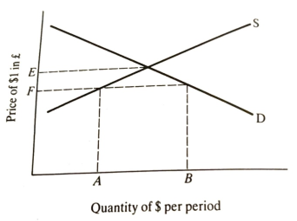

In Figure 6.4 the vertical axis shows the price of $1 in pounds, so going up the axis is devaluing the pound. The horizontal axis shows the number of dollars demanded or supplied in exchange for pounds. As the price of dollars rises UK citizens find the price of US goods has gone up, so they buy less of them. If demand is elastic they will buy both a smaller quantity and a smaller value and will, therefore, demand fewer dollars. In that case, the demand curve for dollars D will be downward sloping for the exchange rate. Even if the underlying demand curve for goods were negatively sloped, the demand curve for dollars would be upward-sloping f the demand for goods were not elastic.

The supply of dollars, S, is upward sloping so long as US demand for UK goods increases, as the pound is devalued. This is the 'elasticities approach' to the balance of payments and it leads to the Marshall-Lerner condition. This is that for a devaluation to improve the balance of payments, the sum of the elasticities of demand for imports and exports must exceed one in absolute value. This is the stability condition for the market depicted in Figure 6.4, since if D were upward-sloping and S downward sloping the market would be unstable in the sense that there would be excess demand above the equilibrium price and excess supply below.

Figure 6.4 Exchange rate determination.

This model is extremely helpful in illustrating why the balance of payments is such a problem when the authorities are trying to peg the exchange rate in an over-valued position, such as at F. Here there is an even demand for dollars, which in this model is the same as a current account deficit, equal to 8-A. The only way that price F can be maintained is by the domestic authorities providing A dollars per period out of reserves by, in effect, buying back sterling of equivalent value Reserves are finite so this position is not sustainable indefinitely. A short-term is to borrow more reserves. A devaluation would involve changing the intervention price to E, but the conventional response in the 1950s and early 1960s was to depress domestic expenditures so that the D curve would be shifted to the left.

How is the monetary approach used to determine the demand of currencies derived from flow demands of goods?

The monetary approach is critical of treating exchange rates as solely determined by flow demand for currencies derived from flow demands for goods. Exchange rates are the relative price of two amounts of money, so conditions in money markets must have some part to play. In a world of mobile financial capital, the critical condition to be met is that all money stocks and financial asset stocks must be willingly held, at the margin. If there are excess money supplies or portfolio disequilibria, then financial capital will be flowing internationally and, in the absence of central bank intervention, exchange rates will be changing.

The principal difference between the fixed and floating exchange rate cases of the monetary approach is that, in the former, the price level was fixed to that of the rest of the world and the nominal money supply could change through induced reserve changes. In the latter there are no reserve changes and the nominal domestic money supply is fixed by the authorities. However, the real money supply is determined endogenously because domestic prices are no longer tied to foreign prices. Monetary expansion by the authorities now leads to downward pressure on the exchange rate and upward pressure on the domestic price level. The exchange rate measures the value of domestic money in terms of other money. The price level measures the value of domestic money in terms of goods. They are both indicators of the same thing declining value of the domestic money. Neither is the cause of inflation, and both are different aspects of the same inflation.

The monetary approach to the exchange rate does not claim that only monetary factors are important, but it does stress the importance of money markets in the short-run determination of exchange rates. This is because it may take a long time for price changes to influence goods markets, but the international 'wholesale' money markets are highly sensitive to minute interest differentials and expected exchange rate changes. If these markets anticipate an exchange rate change, as a result of some policy change. holders will tend to move immediately out of the currency which is expected to decline in value. Floating currencies do not move smoothly in line with inflation differentials. They adjust quickly to new information, but with a tendency to overshoot. The cause of overshooting will be discussed below.

Finally, it is important to avoid confusion about whether the monetary approach is a long-run or short-run theory. The fixed-rate case was criticized by some for only explaining the long-run situation, while the proponents of the floating case espouse it as providing the dominant short-run explanation of exchange rates. It would seem that the behavior of the authorities can change a model from the long run to the short run or vice versa. The answer to this paradox is very simple. In both cases, demand for money for transaction purposes for most individuals and non-financial firms can be out of equilibrium for long periods. International goods arbitrage is also slow so the 'law of one price' or purchasing power parity is at best long-run equilibrium conditions. However, interest arbitrage equilibrium conditions between financial firms such as international banks hold almost exactly even in the very short run. The monetary approach in both fixed and floating exchange rate cases is a theory of short-run international portfolio adjustments, i.e. capital flows. These markets adjust most quickly and can thus dominate exchange markets in the short run. They are thus vital components to the explanation of short-run exchange rate changes in one case and reserve changes in the other.